The Institute of Race Relations

Why is an "anti racism think tank" so proud of its connection to Pol Pot?

Welcome to the SW1 Forum, a newsletter about British politics and everything wrong with it.

Introduction

Are authoritarian English schools criminalising and excluding black working class pupils in order to “blunt the political aspirations for racial and social justice within multiracial working-class communities”? That is the claim made in a recent article by Jessica Perera, an Oxford DPhil candidate who works as an Associate Researcher with the Institute of Race Relations, a well-established British charity which calls itself an “anti racist think tank”.

The article is a summary of a research paper Perera wrote for the IRR; a close reading of them reveals some unusual statements. For a start, Perera explicitly hopes that her paper will support activists pushing to “decolonise education”. Her definition of what constitutes political activity for black working class pupils includes “urban uprisings”, otherwise known as riots. She doesn’t answer “black and brown” critics of a “social justice curriculum”, dismissing them instead as “compradors”. That unusual term is defined by the Oxford University Press as “a person who acts as an agent for foreign organizations engaged in…political exploitation”. That’s a very loaded term to use to describe critics, especially without any proof. Finally, at the end of her article, she calls on the left to question this system “because this is the battleground where hearts and minds are won, and we cannot afford to lose this war”. With that “we” she identifies herself in a very unsubtle way with the left.

This isn’t an isolated incident, as Perera previously wrote an approving article for the IRR on Grime artists who backed Jeremy Corbyn (support which most subsequently revoked in 2019). Even though the rules on charities and political activity are vague, the IRR has a long history of pushing the boundaries.

What is the Institute of Race Relations?

The IRR was founded with a very different purpose in 1958, when it was known as the Race Relations Unit. The idea for the organisation was suggested by the editor of The Sunday Times, who thought that Britain needed to keep an eye on its ex-colonies as it slowly withdrew from Empire. The initial focus was therefore on race and communism before moving into domestic research; their report Colour in Britain was supposedly the first study of race relations in Britain. Their establishment connections are summed up by the IRR’s chairmanship by Sir Alexander Carr-Saunders, a noted LSE eugenicist.

By the 1970s Britain was facing major social change, not least the existence of growing domestic populations of non-white people and an increased left-wing interest in the subject of liberation politics. Within the IRR that led to a growing divergence between some of the staff and the leadership. The staff argued that the IRR wasn’t impartial because of its reliance on government and business funding, demanding that they be biased in favour of the victims of racism instead. When the governing Council tried to shut down the IRR’s magazine Race Today over its supposed bias, the staff rebelled. At the 1972 extraordinary general meeting they outvoted the Council, which resigned en masse. The IRR lost most of its funders but had transformed itself in the “anti racist think tank” it remains today. They soon found new funders, like the World Council of Churches (which was heavily infiltrated by the KGB at the time).

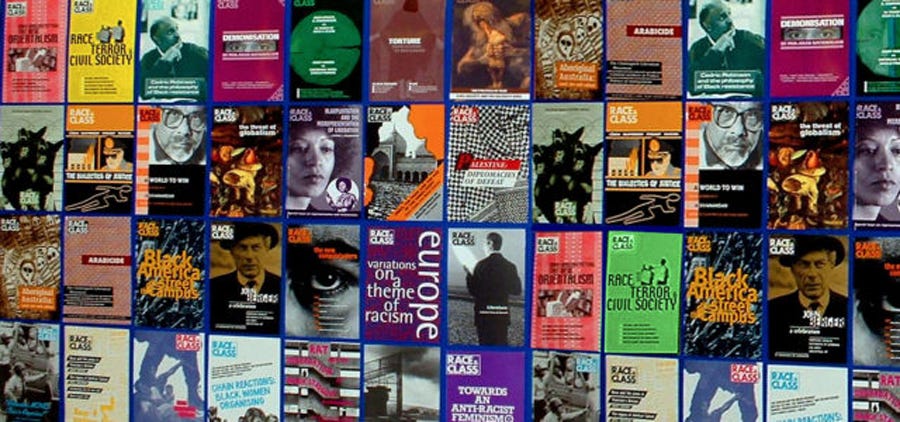

Since then it has focused on researching “contemporary British racism”, publishing the quarterly journal Race & Class, and disseminating information from its Black History Collection. They also publish regular reports on race in Europe and a news service on racial issues.

What does the IRR believe?

The IRR brags on the page about the history of their Race & Class journal that three contributors were “killed in the front line of struggle” of the “liberation movements”. The first, the assassination of the Chilean economist Orlando Letelier by agents of Pinochet may well count. The second is Guyanese Marxist academic Walter Rodney, who was blown up on his return from independence celebrations in Zimbabwe. His death remains less clear, with evidence suggesting that he was killed on the orders of Forbes Burnham, the strongman socialist leader of Guyana.

The most striking inclusion is the third, Malcolm Caldwell. A Scottish academic at SOAS, he was one of many on the left who denied the existence of the “killing fields” in Cambodia, in which the communist government killed around 1.5-2 million of their own people. Caldwell’s naiveté led him to travel to Cambodia in 1978 to meet Pol Pot, the dictator of the country, only to be murdered a few hours later, probably as part of an internal party struggle. However sad his end, Caldwell died as an active defender of a murderous regime. If the politics were swapped, it’s hard to imagine any magazine bragging that amongst its alumni was a Holocaust denier, even if neo-Nazis probably killed him.

Nor is this an isolated example of misjudgement. Amongst the long-term staff of the IRR is Jenny Bourne, who has written an article on the Spaghetti House Siege. This obscure incident in 1970s London saw three supposed black liberation activists try to rob a restaurant in Knightsbridge. When things went wrong and the police surrounded them in the restaurant, they took hostages. Eventually they realised their position was hopeless and surrendered, although one shot and failed to kill himself, before all were tried and imprisoned. Two of the three activists had records of petty crime and one of their accomplices, who was also jailed, supposedly planned the robbery to help him pay off gambling debts.

Bourne’s focus however is to “set the record straight” by demonstrating that, far from being the work of bungling petty criminals, it was in fact a political act. She knows this because one of the three criminals was Wesley Dick, who was a volunteer with the IRR at the time and often frequented their library (as well as using their phone to ring his girlfriend). He was a regular reader there of Black Power newspapers like The Black Panther (the paper of the Black Panthers, who’d been involved in numerous deadly shoot-outs with police) and Muhammad Speaks (the paper of the Nation of Islam, which is called a hate group by the SPLC). At the same time, Dick was refurbishing old firearms with some others, intending to send them to third world guerilla movements like ZANU and FRELIMO (both of which were responsible for numerous war crimes and which promptly turned into dictatorships on winning power).

To give some idea of how close the IRR was to Dick, when British Black Power groups like the Fasimbas and the Black Unity and Freedom Party issued a joint statement on the siege, amongst the other signatories were Race Today (which had broken away from the IRR in 1973 to become a fully Marxist magazine published by a collective in Brixton), A. Sivanandan (who was the IRR’s librarian at the time), Leighton “Darcus” Howe (a British Black Panther, who at his trial for riot and affray demanded an all-black jury whilst his co-defendants tried to punch the police officers guarding them) who was the editor of Race Today at the time, and John La Rose (who had been the chairman of the IRR from 1972-73). They were part of a broader social network which included Leila Hassan (the IRR’s Information Officer, who was also a British Black Panther and BUFP member), Farrukh Dhondy (also involved with the British Black Panthers and Race Today, who would later become a long-serving Channel 4 Commissioning Editor), and Olive Morris (a British Black Panther who co-ran Race Today’s “Basement Sessions” and campaigned on behalf of FRELIMO, Maoist China, and Angela Davis; Lambeth Council named one of their offices after her and she is featured on the Brixton Pound).

The joint statement blamed the actions of the three robbers not on themselves but on the “miseducation of black children”, “housing conditions in the black communities”, and “unemployment among… black youths in particular”; it went on to support the robbers' demand for a plane out of the country.

Once in prison the three robbers fell in with imprisoned IRA terrorists, who persuaded them to refuse legal representation and to signify their rejection of the legitimacy of British courts by turning their backs on the judge. All were sent to jail. Bourne adds that she and other members of the IRR “were to visit regularly” one of the prisoners over the next 12 years. Considering that the official aim of the IRR is to “improve” the relations between “different races and peoples”, it’s hard to see how supporting violent Black Power activists and continuing to defend them in print achieves that.

Today the IRR remains radical, calling for “divesting from immigration policing”. In practice this means “an end to laws that, in criminalising those who cross borders ‘illegally’, drive them [immigrants] into the arms of traffickers”. In addition, they call for “an end to the ‘culture of disbelief’” when it comes to asylum cases. The money saved from ending “militarised borders” meanwhile could be used to fund things like the search and rescue ship Iuventa (whose crew are facing 20 years in an Italian jail over claims they colluded with people traffickers to transport people from Libya). This effectively means open borders, asylum for anyone who claims it (even if their case is absurd or provably false), and government funding to facilitate mass migration. There is no suggestion that this should be decided democratically first.

How does the IRR work?

Examination of the IRR’s funds show that in the financial year ending on 31st March 2019, their income was £281,771. Of this, only about a sixth came from donations, with the majority being provided in the form of grants and income from their journal Race & Class. Most of the grant money was provided by the Open Society Foundation and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Over £3,000 of income came from reclaimed gift aid; in others words, from public money. Race & Class earns most of its money from university subscriptions - only £1,190 a year if you want access to their full back catalogue - and is therefore also effectively subsidised by the taxpayer.

This money is then overwhelmingly spent on wages - £165,446 of the £240,284 spent in 2019 (not including a termination payment of £14,272, social security costs of £12,566, and pension costs of £4,626). No other costs reaches five figures, with the rest of the spending mostly on IT, venue hire, and legal costs.

Comment

When looking at how the IRR spends its money, it is clear that there is little grassroots demand for the IRR. Nor does it spend its income on directly helping others. Rather, it is the work of activists and academics, who use it to push a one-sided politics whilst flirting with violent political extremists and divisive rhetoric. All the while it is funded indirectly by the universities and directly by unaccountable foundations. It is time for the British state to look seriously at the laws governing charities, if they feel that it is somehow appropriate to brag about their connections to Pol Pot defenders and armed robbers.

If you enjoyed this newsletter then please subscribe below - there will be a new one every week.